Living and working in Zhaoqing - „a small city”

When my Chinese students use the phrase a small city, I always correct them. It does not seem like a natural collocation. Cities can be bigger or smaller, but I used to think that they are never small. You can say a small town, yes. But not a small city. Well, the perspective changes when you know what is big and small in China. I come from a country the capital of which has around one-and-half-a-milion population. I come from a city the population of which is around five hundred thousand – much less than Zhaoqing – and it is the fifth biggest city in Poland. But when you compare Zhaoqing to a nearby Guangzhou, it is definitely not big. So, how should we call it? It is definitely too big to be called a town, yet, according to Chinese sense of measure, it is small. Maybe we should make an exception and call it a small city?

Zhaoqing University

When it comes to measures, Chinese space management is still a mystery to me. See the lanes of Guangzhou, with dozens of tiny shops and restaurants packed so densely, that you almost lose an idea where one starts and the other finishes. Also, when I look at the streets, I always ask myself: what ELSE can you transport on a moped/ motorcycle/ bicycle? I have already seen: a plant in a flowerpot; a puppy (no cage, just lying between the driver's feet), a one and a half meter high floor lamp, some cardboard (transported loose, on the driver's knees)... And no one gets hurt, there is no accident, nothing falls down nor gets broken. I have not seen any furniture yet, like a chair or a wardrobe, but I would not be surprised.

Guangzhou

I guess a perfect sense of balance is the key. Well, not only a physical balance. Also mental balance. There is a railroad crossing at the university. Each time the bar is going up, a crowd of drivers, cyclist and pedestrians try to get through a narrow gulf of the lane at the same time, like a swarm of honey bees. I have seen that scene many times, but I have never seen any slightest sign of road rage. In my home country, whenever the street is dense with cars or people, once in a while there appears somebody who gets furious with the slow pace or traffic jam, rolls a window down and shouts: What are you doing? Where are you going? No such thing here. If a bus driver rolls a window down, he does it to have a quick chat with another bus driver waiting at the traffic lights.

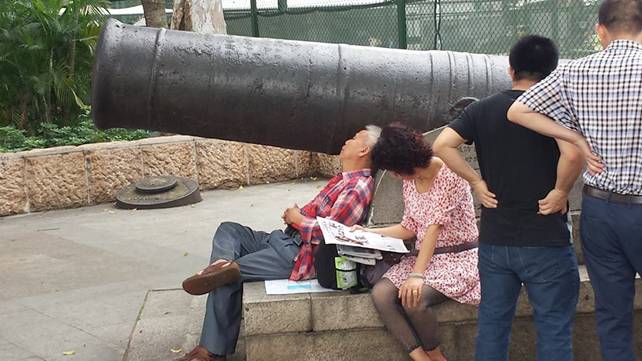

Guangzhou. So calm a cannon would not wake him up.

Yes, a sense of balance. Calmness. This is something you can learn from the Chinese. Apparenty, that is how the literal translation of the word Zhongguo suggests. The middle country. The country of balance. And what can you learn from Chinese students? An exciting thing about teaching in another continent is that you broaden your horizons not only finding out what people know about their world, but also learning what they do not know about your world. You get surprised in the beginning why the student who can use advanced words, like low-carbon instead of green does not know the word cutlery? But then, why he should know it if cutlery (i. e. a fork, a knife and a spoon) is no way a basic concept here?

Also, you need to explain why English and Polish people's daily job is their daily bread while Chinese people's dailyjob is their fanwan. You introduce the icons of English language culture, like Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley, which do not need introduction in Europe. At the same time you try to remember the names of their idols, check them in the internet browser, try to get the grip of what fascinates them. On the one hand, this is a real eye opener. This is what makes you realise more the richness of the world and how much you need to learn about it. On the other hand, you make them open their eyes into your culture, your world, your worldview. This is what teaching should be for students. This is what teaching should be for a teacher: always getting surprised with new people, new worldviews, new encounters.

My students, during oral English class

Not to mention technical things, which improve your teaching workshop. I have never worked with so big oral English groups. I have never worked in an environment when the students do not understand my mother tongue – when I worked in Poland, the language of the classes was, of course, English, but there is always a safety net, in case the student really could not get what I was saying. Then we could switch to Polish (we very rarely did that, though). No such possibility here (after only three months in China my Chinese is very, very poor). This is another teaching workshop challenge: always work on the clarity of your instructions.

What helps is the attitude of students. Many of them have a really childlike curiosity and eagerness to learn new things. In Poland, in my short, six-year teaching career, I had many fascinating encounters with people, many challenges, many students working hard and motivated. But I have never had an applause after classes. Here? Two times, in three months. Nothing motivates better.

Me and my students, during oral English class

When I came here three months ago, the air was really hot and damp. For the first few days the sky felt so heavy that you had an impression that in a minute a torrential rain was going to fall. It did not happen, though, at that time. Just a dense air that made you sweat and difficult to breathe. Nevertheless, despite the humid and dense air of tropical summer, I can already call my teaching contract in China one of the most refreshing experiences in my life.

Jakub Sajkowski, male, 30 years old, Poland, teacher of English